A new era for neurodegenerative disease

30,000

The number of patients with ALS, 2016

6,000

New cases of ALS each year

Medical advances now mean that people are living longer than ever before. But while this is a wonderful achievement, increased mortality has come with an unexpected downside. Over the years, neurodegenerative disease has risen dramatically.

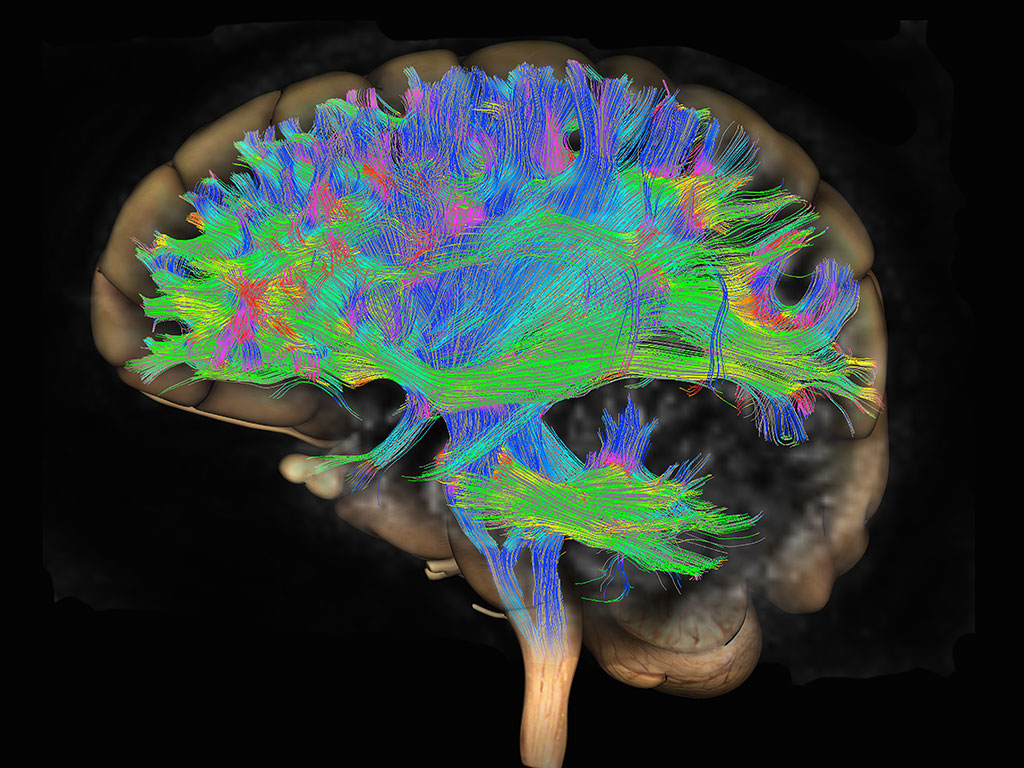

This umbrella term describes painful, debilitating and – ultimately – fatal conditions that are typified by the dysfunction of neurons in the brain. Neurons are vital to survival and essential in the nervous system, which communicates messages from the brain and spinal cord to parts of the body.

They, too, are finite and delicate. When neurons die, the body is unable to replace them. And so the prognosis for illnesses that compromises them is grave indeed.

Some of the most common diseases associated with neurogenic dysfunction include Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS – better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease). All of these have grim prognoses for individual sufferers.

Perhaps one of the most rapid neurodegenerative diseases is ALS, which became highly publicised thanks to the recent social media phenomenon: the Ice Bucket Challenge. ALS is a progressive, deadly affliction that attacks neurons implicated in muscle movement. As these neurons shut down, the body does too. Over half of patients with a diagnosis die three years later.

Neurodegenerative diseases like ALS and AD are not only a death sentence, but provide weeks, months and years of mental and physical pain, as well as financial strain, for those afflicted and their loved ones.

Even worse is that they show no signs of going away: statistics from ALS Association show that there are currently 30,000 patients with the disease – and 6,000 new cases each year. Alzheimer’s deaths have increased by 71 percent over the last decade. The numbers grow all the time.

The challenge

Treatments for neurodegenerative disease have been slow to develop and largely unsuccessful

Ageing populations have made neurodegenerative disease a ticking time bomb

In spite of the prominence of neurodegenerative disease, scientists have had an enormous task on their hands combatting them. These are complex disorders, requiring nuanced approaches, and thus solutions have been slow to arrive.

During this time, both ALS and other neurological diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, have remained incurable and impossible to prevent, slow or reverse. The only drug available for ALS, approved almost two decades ago, offers just two to three extra months of survival.

For too long scientists focused on methodologies that did not work; after 20 years examining SOD1, the first gene implicated in ALS, scientists are still searching for a cure. Since SOD1 is only responsible for two percent of ALS cases, the majority of patients are still seeking new approaches.

Ageing populations have made neurodegenerative disease a ticking time bomb. The National Institute on Aging anticipates that there will soon be more people in the world over the age of 65 than under five. For many, old age will not be a blessing, but a curse. By 2025, researchers expect the number of people with Parkinson’s to double from its 2005 level to 8.7m; Alzheimer’s will triple by 2050, and ALS to increase by 70 percent.

Overall, the science of neurology – by virtue of its difficulty – has struggled to find answers to some of today’s biggest medical problems. New treatments are urgently required to solve neurodegenerative disease, and give people their lives back.

The stress granule pathway

The stress granule pathway has been identified as one of the most significant factors in ALS

8.7m

The number of of people expected to have Parkinson’s in 2025

TDP-43

A protein that creates stress granules, present in ALS patients

Enter Aquinnah Pharmaceuticals. This innovative company in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has offered some of the most innovative, promising solutions to ALS and AD in recent years – which could have far-reaching consequences for all neurodegenerative diseases.

The company was founded by Dr Ben Wolozin and Dr Glenn Larsen, two decorated and experienced scientists, who believe they are on the cusp of a major breakthrough in neuroscience; a golden age, in fact.

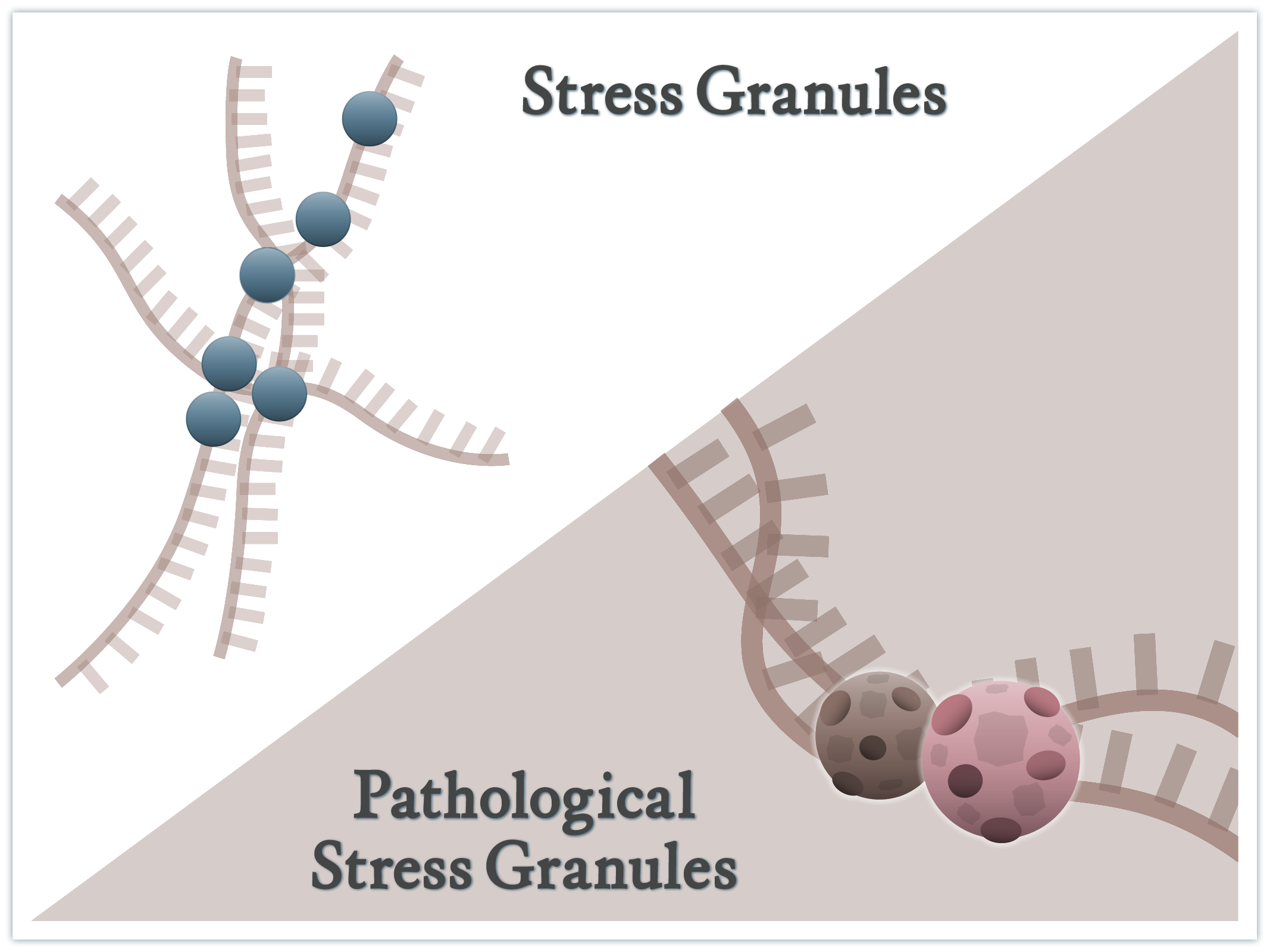

Their research focuses on the hypothesis that solving ALS and Alzheimer’s (and even other neurodegenerative diseases) lies in eliminating persistent stress granules. These are biological gatherings of proteins and mRNAs (messenger ribonucleic acid), which help the body to repair itself.

When a healthy body gets injured, it creates stress granules to restore the damage. After the body has fixed itself, the stress granules disperse. In cases of neurodegenerative disease, stress granules are stickier and stay around longer. They may build up in specific parts of the body, whether it’s the spinal cord (ALS), or the hippocampus in the brain (Alzheimer’s).

Wolozin was the first to spot the potential of stress granules as a cure to neurodegenerative disease, quite by chance. They’d been brought to his attention by a colleague, working in a separate field. Some time afterwards scientists discovered that TDP-43, a protein that creates stress granules, was present in ALS patients.

These two separate events inspired Wolozin to probe further into stress granules. He thought that if he could manipulate and understand them, he might be able to change whether or not they stuck together – which is the precursor to neurodegenerative disease.

De-stressing the pathways

Stress granules can either be useful or a hindrance depending on their persistence

Aquinnah is the only one to actually undertake tests on how to eliminate stress granules

Since then, Wolozin and his colleague Larsen have employed an elite team at Aquinnah’s headquarters to help them on their mission – to eliminate persistent stress granules. To this date they have tested over 75,000 compounds and have found several promising candidates.

Through its work, Aquinnah has been able to develop a number of candidates for drug development, created using compounds that can tackle stress granules – and be orally administered.

Over the years there’s been a lot of talk, but little action, about stress granules. On the whole, scientists know that dysfunctional stress granule proteins are the main cause of ALS – present in over 90 percent of patients – and estimated in 50 percent of Alzheimer’s cases.

But Aquinnah is the only one to actually undertake tests on how to eliminate them. Its scientists have already started animal trials to test the compounds, with human trials scheduled in the next two to three years.

Because ALS is such a rapidly progressing disease, it should only take the team a year to discover whether the method works in patients. Should this be the case, similar trials for Alzheimer’s will soon follow.

An elite team

The team is determined to eliminate ALS and other terrible neurodegenerative conditions

15

The number of drugs Larsen has brought to clinical development

5

The number of drugs he has brought to the market

The Aquinnah team’s academic credentials are as great as its determination. The company’s Co-founder and CEO, Larsen’s, unique blend of scientific knowledge combined with business acumen (a PhD in biochemistry and a PMD from Harvard) has proven a winning formula throughout his career. To date he’s helped bring 15 drugs to clinical development and five to market – with sales of over $10bn.

His fellow Co-founder and Chief Scientific, Wolozin, has an MD and PhD degree, and extensive experience in drug development. Among his discoveries was one of the first molecular markers for the tangle pathology that causes neurons to gather in Alzheimer’s disease. His lateral thinking also saw him become one of the first to hypothesise that statins have a protective effect against the same condition.

Both men are united in their passion to help others, and see genetics as the future for curing neurodegenerative disorder. Speaking about the team’s approach, Wolozin said: “Genetics is nature’s way of telling you what’s wrong. When you understand the machine, you can begin to repair it.” This they intend to do through drug therapy.

Aquinnah achievements

Aquinnah has gained rich acclaim for its research into stress granules

Aquinnah has won wide acclaim for its impressive research

Throughout the years, Aquinnah has won wide acclaim for its impressive research. Wolozin’s discovery of persistent stress granules in ALS and Alzheimer’s disease makes him not only a leading light among colleagues, but among those affected by such conditions. He has won many awards for his work, including the prestigious Zenith Fellows Award and the A.E. Bennett award from the Society for Neuroscience.

For its research on ALS, Aquinnah has been awarded four peer-reviewed grants over 2016 – two from the ALS Association, and one each from the National Institute of Health and the Massachusetts Life Science Center. Leading pharmaceutical companies, such as Takeda Pharmaceuticals, have also given support to the company.

The huge progress that the Aquinnah team has made in the scientific field, paired with each scientist’s academic knowledge and techniques, has made them not just hopeful, but confident, a solution to ALS is on the horizon. This, in turn, should have widespread implications for all neurodegenerative disorders – and bring scientists closer to ending the terrible diseases that continue to plague, what otherwise is, a golden age for neuroscience.